“The most dangerous man to any government is the man who is able to think things out for himself, without regard to the prevailing superstitions and taboos. Almost inevitably he comes to the conclusion that the government he lives under is dishonest, insane and intolerable, and so, if he is romantic, he tries to change it. And even if he is not romantic personally he is very apt to spread discontent among those who are.”

– H. L. Mencken

For reasons I can’t quite fathom (although it might have been more than one person professing their undying love for Watchmen to me in the space of a week), I took the time this week to explore a medium that I had long neglected: comic books. This first foray took the form of the postcyberpunk comic Transmetropolitan.

For reasons I can’t quite fathom (although it might have been more than one person professing their undying love for Watchmen to me in the space of a week), I took the time this week to explore a medium that I had long neglected: comic books. This first foray took the form of the postcyberpunk comic Transmetropolitan.

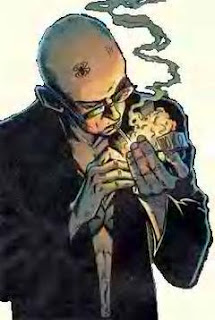

I was very impressed; Transmetropolitan follows the Hunter S. Thompson-esqe gonzo journalist Spider Jerusalem on his mad quest for truth in the politically corrupt world of the future. It deals with themes of dissent, censorship, propaganda and journalistic integrity, and is a profoundly human drama (absent of solipsistic robots and intergalactic space battles.) Furthermore, it’s nice to see a hero armed with nothing but a typewriter, a lot of drugs and the truth.

I could say more, but to be honest I’m still letting what I’ve read swirl around in my head a little. I will however say that if, like myself, you haven’t opened up a comic book in over a decade, Transmetropolitan seems like a decent place to start.

Since I enjoyed Transmetropolitan so much, I went ahead and ordered a few graphic novels off Amazon.ca, namely Watchmen, V for Vendetta and The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen. Those should be arriving towards the end of January, and I’ll be perusing Y: The Last Man until then.

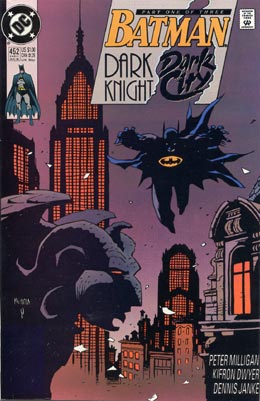

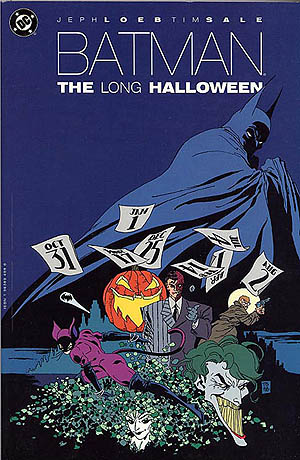

While I’m a relative neophyte to the world of comics, I’ve become a rather big fan of two series: Mike Mignola’s Hellboy and Jeph Loeb’s Batman stories (such as

While I’m a relative neophyte to the world of comics, I’ve become a rather big fan of two series: Mike Mignola’s Hellboy and Jeph Loeb’s Batman stories (such as  As part of my

As part of my  For reasons I can’t quite fathom (although it might have been more than one person professing their undying love for

For reasons I can’t quite fathom (although it might have been more than one person professing their undying love for