Diagram via LoL Esports

Diagram via LoL Esports

Back in 2011, a friend gently guided me through the steep learning curve of League of Legends, and I’ve been playing it on and off ever since. For about as long, I’ve been casually following the competitive LoL esports scene, especially enjoying the Worlds championship tournament that caps off each year. Worlds 2023 has been particularly great thanks to a big change: Riot Games replaced the traditional “groups” stage with a “Swiss” format stage instead. Examining this change through a game design lens helps reveal why it has been so successful and impactful.

For years, the essential structure of the Worlds tournament has been the same. In the “groups” stage, teams are randomly drawn into smaller groups (usually four groups of four), and the top two teams from each group advance to the “knockout” stage quarterfinals. In 2014, the concept of “pools” was added so that teams would be seeded for groups based on their regional standings. This structure has worked reasonably well and created some terrific memorable tournaments, but one persistent awkward issue has been the randomness of the initial groups drawing.

For game designers, randomness is a tool and not necessarily a bad thing. It’s also not a unitary property; there are many different flavours of randomness, as I explored in a previous article about card design in Hearthstone. For designing a tournament, there are many upsides to randomness: it has the potential to create exciting matchups and surprising upsets, and a random draw is “fair” to all competitors.

However, a tournament has two primary objectives: to crown the best team based on skill, and to showcase exciting matches for the spectators. The fact that the initial random drawing for groups has an outsize impact on the overall outcome is inimical to both of these goals.

Because of the large skill discrepancies between teams and regions, the chance placement into groups can effectively predetermine who will advance. In mathematics this is called “sensitive dependence on initial conditions”. For instance, sometimes four strong teams are drawn into the same group. This creates a fiercely competitive “group of death” with a hard road for any of them to advance to quarterfinals. The opposite is an unbalanced “group of life” with two strong teams and two weak teams. This produces boring one-sided matchups and a practically foregone outcome. Even worse, it can set up pointless matches for teams that have already been mathematically eliminated.

From a game design perspective then, what is the fundamental flaw here? To quote Mark Rosewater: “randomness cannot be the destination; it has to be the journey.” Randomness is fun when players have a chance to respond to it. An ideal tournament format would not sharply delimit the range of possible outcomes with the initial random draw, but instead empower teams to change their destinies through their hard fought victories and defeats. From the spectator’s point of view, it should also produce close matchups and provide high stakes.

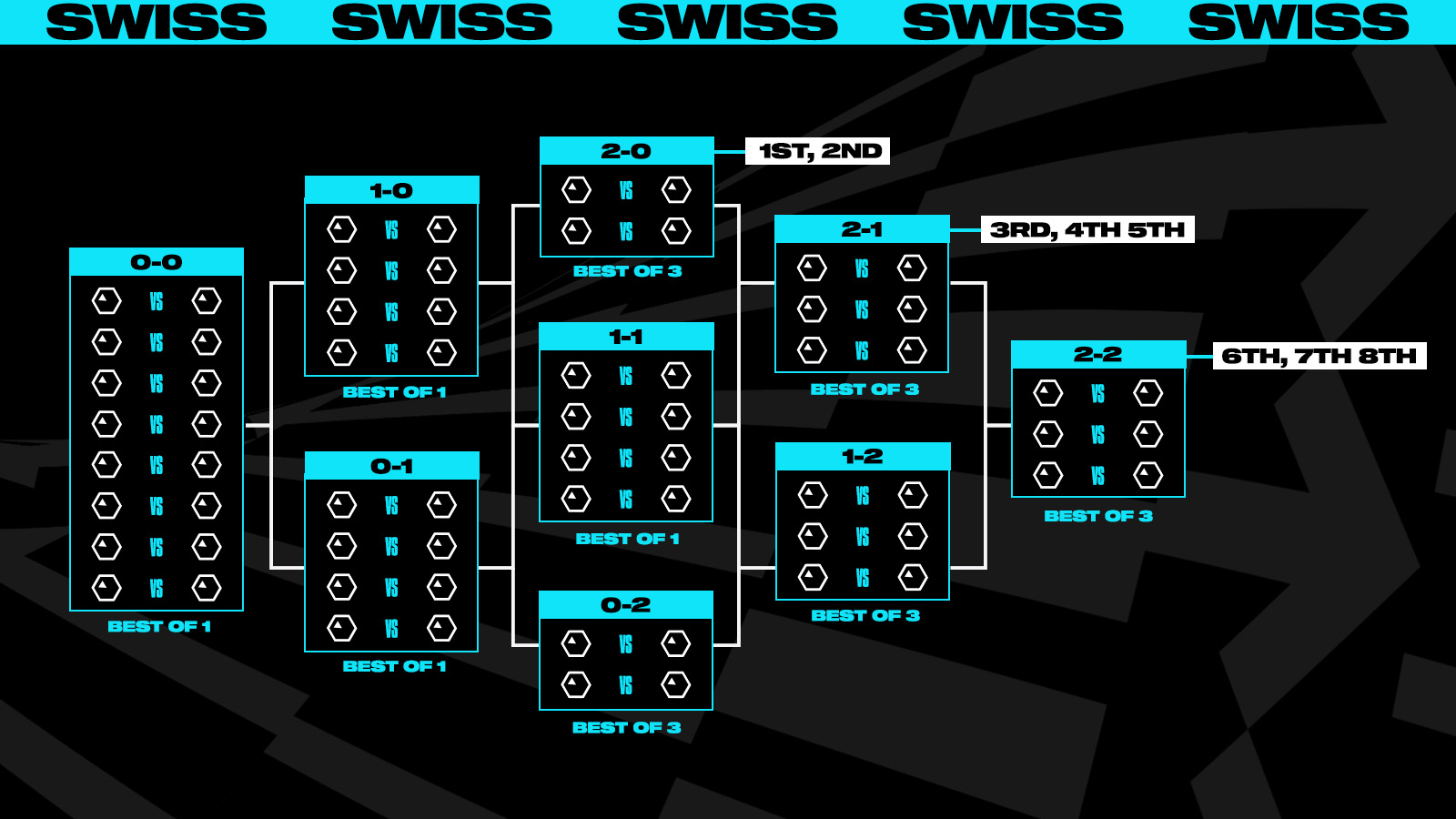

For comparison, let’s examine the “Swiss” stage which replaced the “groups” stage at Worlds 2023. The structure of this format was developed in the 1890’s for chess tournaments. In the first round, teams are randomly paired (against a region other than their own). In each subsequent round, teams are randomly paired against teams with the same win-loss record. This continues for five rounds until each team advances (with 3 wins) or is eliminated (with 3 losses); elimination and advancement matches are best-of-3.

For example, in round 3, there will necessarily be four teams with 2 wins, eight teams with 1 win / 1 loss, and four teams with 2 losses. A random draw will pair each team against another team with an identical win-loss record. A 2-0 team that wins advances to the next stage; a 0-2 team that loses is eliminated. All other teams continue into round 4 with either a 2-1 or a 1-2 record, and those records determine the next random pairing.

This structure provides a beautiful mix of positive and negative feedback that any game designer would recognize approvingly. Teams that win get closer to advancement, but also place themselves into the more competitive “group” of other winners (negative feedback). When winning teams qualify for the next stage, they no longer stick around to act as spoilers for the remaining matches (negative feedback). On the other hand, weaker teams eliminated early no longer provide “easy wins” (positive feedback).

Note that both formats rely heavily on random drawings for determining matchups. The critical difference is that the “groups” format fully resolves all randomization before the first match is played. In the “Swiss” format, something teams can control (their win-loss record) is fed back into the randomization. Teams are no longer trapped in groups of life or death, but chart a course through “fair” matchups driven by their skillful play.

Note that this format does not eliminate “luck” in draws; compare NRG’s easy path through the Swiss stage with KT Rolster’s slog. Recall, however, that a tournament has a second primary goal: to create excitement for the spectators. In this regard, the Swiss format has two significant benefits.

Firstly, the format optimizes for matchups between teams that are close in skill. The strongest and weakest teams quickly diverge into separate trajectories, reducing the odds of a one-sided stomp as the tournament advances. Secondly, it ensures that every match is meaningful to the outcome of the tournament. There are no lopsided groups or predetermined outcomes; every match is a fight to advance or a fight to survive.

Games that incorporate randomness need to do so with great care and intentionality, and it’s been fascinating to see a “metagame” of tournament design incorporate those same design considerations. Riot Games deserves credit for shaking up their longstanding competitive structure, and I’m excited to continue following Worlds 2023 through the knockout stage.