This summer I’ve been casually following Game Design Concepts, Ian Schreiber’s experimental online game design course. The curriculum has covered a number of thought-provoking concepts, but the real light bulb moment for me came in his discussion of the MDA framework1.

Robin Hunicke, Marc LeBlanc and Robert Zubek defined MDA in 2001 [PDF link]. It stands for mechanics, dynamics and aesthetics, the three layers that define a game. These words are often thrown around casually in game design discussions, but in MDA they have very specific meanings:

- Mechanics are the formal rules of the game. These rules define how the game is prepared, what actions the players can take, the victory conditions, the rule enforcement mechanisms, etc.

- Dynamics describe how the rules act in motion, responding to player input and working in concert with other rules. In programming terms, the “run-time” behaviour of the game.

- Aesthetics describe the player’s experience of the game; their enjoyment, frustration, discovery, fellowship, etc. In simple terms, what makes the game fun?

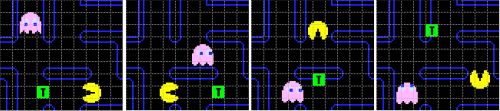

We can illustrate these concepts with the classic game Pac-Man. The pathfinding logic of the enemies is defined by a formal set of rules. Each ghost has a unique seeking mechanic: Blinky targets the tile that the player currently occupies, while Pinky targets four tiles ahead. Together, these rules create a dynamic wherein the player becomes boxed in by Pinky in the front and Blinky from behind. The enemy dynamics present a challenge to the player, creating an aesthetic of fun and excitement.

In his post on MDA, Schreiber also offers the following example:

In a First-Person Shooter video game, a common mechanic is for players to have “spawn points” – dedicated places on the map where they re-appear after getting killed. Spawn points are a mechanic. This leads to the dynamic where a player may sit next to a spawn point and immediately kill anyone as soon as they respawn. And lastly, the aesthetics would likely be frustration at the prospect of coming back into play only to be killed again immediately.

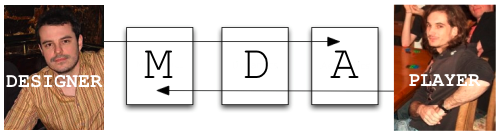

As illustrated above by Clint Hocking2 (lead designer of Far Cry 2) and Ben Abraham (blogger, musician, Far Cry 2 enthusiast), designers and players experience games from different perspectives.

Game designers only have direct control of the game’s mechanics; the mechanics work together to generate the dynamics, which in turn generate the aesthetics. They want to make their games fun and engaging, but only have indirect control of the player’s experience. Schreiber calls this a “second-order design problem” and it’s the reason why game design is challenging. Thus, designers tend to see mechanics and work outwards.

Conversely, players are immediately familiar with their own emotional response to a game regardless of whether they understand the underlying rules. One can enjoy Wii Sports tennis without necessarily knowing the exact dimensions of the virtual court. Only through hours of observation and deduction do the dynamics and mechanics gradually become clear.

We can see the contrast between these two perspectives in Clint and Ben’s writing about Far Cry 2. Clint’s GDC 2009 presentation reveals how the game inflicts “random, small losses” in order to keep the player alternating between “composition” and “execution”. This explains how the attrition mechanics create dynamics that force the player to improvise, resulting in a challenging and immersive aesthetic. Ben, on the other hand, insightfully chronicles the aesthetics of games. This does not imply that his appreciation is shallow, rather that he sees games in terms of personal experiences and emotional responses rather than abstract systems of rules.

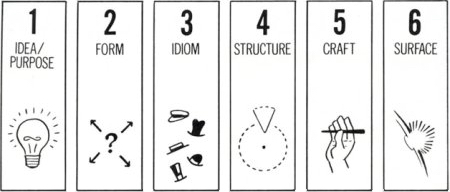

How do the three layers of MDA compare with the six layers of art proposed by Scott McCloud? Schreiber suggests that they are nearly parallel: “mechanics are roughly equivalent to […] structure; dynamics are analogous to craft; and aesthetics are similar to surface.” While there is ostensibly strong similarity between the two frameworks, I believe that they diverge on a crucial point.

McCloud’s six layers of art are ranked according to importance; novices concern themselves with surfaces while masters concentrate on ideas and forms. Schreiber compares aesthetics to McCloud’s concept of surface, which are the “production values, finishing, the aspects most apparent on the first superficial exposure to the work”. However, McCloud defines ideas, the innermost layer of art, as “the impulses, the ideas, the emotions, the philosophies, the purposes of the work”. This is also strongly analogous to MDA’s definition of aesthetics3. The idea that the innermost and outermost layer are so strongly related is irreconcilable within McCloud’s strongly ranked framework; why then do aesthetics make perfect sense within MDA?

I suspect the reason is that, while MDA’s three layers are also ordered, they are not ranked according to importance or value. Mechanics, dynamics and aesthetics are equally valid and interesting perspectives for understanding a game. While surface is superficial and inconsequential, aesthetics describe concepts that are crucial to an artistic study of games: sensation, discovery, fellowship, expression, challenge, narrative, etc.

McCloud’s six layers of art and MDA are both useful ways of understanding and deconstructing video games. However, this fundamental difference prevents us from drawing easy parallels between them.

1 Months ago Nels recommended I read about MDA, good advice I managed to completely forget. Apologies!

2 Correction: CLINT HOCKING.

3 One could argue that McCloud’s idea/purpose refers to the emotions and impulses of the creator, not the player.

August 21st, 2009 at 2:17 am

Interesting, it sounds like dynamics in the MDA framework is pretty much analogous with more commonly used phrase ’emergent gameplay’.

I think you’re spot on about MDA not being a strict ranking system given that aesthetics is often where things like theme and emotional resonance emerge.

Although I can think of at least one possible exception: In games like Jason Rohrer’s Gravitation the theme and meaning emerge only through replay as the player gradually becomes aware of the dynamics and mechanics behind the game.

August 21st, 2009 at 8:39 am

I first learned about MDA a few years back at the Game Design Workshop at GDC and it totally cemented my design philosophy. I think it is the one paper all designers should have to understand.

August 21st, 2009 at 11:11 am

“One could argue that McCloud’s idea/purpose refers to the emotions and impulses of the creator, not the player.”

That’s the way I interpreted it when I read “Understanding Comics”, that the idea/purpose refers to the reason the creator wants to make the work, or the ideas they want to communicate. I never got the idea that the six steps were ordered by importance, though. They seem to be ordered by when they come in the process of creation, and the reverse order of how they are usually learned.

The main difference I see between mechanics/dynamics/aesthetics and the structure/craft/surface is that while you can change the craft or surface of a work, you can’t directly manipulate the dynamics or aesthetics of a game design, since they follow from the mechanics.

August 23rd, 2009 at 8:09 pm

@Miguel: I can think of other exceptions as well. For instance, a player must learn the mechanics of chess before grasping the dynamics. I’d like to address some of these criticisms and limitations in a future post.

@Zack: It was indeed eye opening, I suspect it’s standard curriculum for game design classes.

@Henk: It’s tricky, but I would argue the following: the emotions of the designer and the player are not completely distinct. If the game succeeds in conveying the creator’s emotions, the player will feel the same way (aesthetic).

Pages 172-184 of Understanding Comics show how amateurs concern themselves with surfaces while master artists work their way inwards. McCloud even states that many great artists spurn surfaces in favour of craft, etc. In this sense, he is ordering them according to artistic importance.

I agree that the second order manipulation problem is another big difference between McCloud and MDA.

August 29th, 2009 at 6:01 pm

[…] Quixotic Engineer: Mechanics, Dynamics & Aesthetics Matthew Gallant gets deep in design theory to outline the inverse perspective between player and […]

August 30th, 2009 at 6:03 pm

Haha! I’m just glad I don’t have to kick myself for failing to suggest this to you before =)

September 9th, 2009 at 2:40 am

[…] MDA: A Formal Approach to Game Design and Game Research The Quixotic Engineer – Mechanics, Dynamics & Aesthetics Filed under: Design, Indie […]