This is an entry in the June ’08 Round Table discussion. This month’s topic, “I Wanna Hold Your Hand”, asks you to explore a relationship within a game that you found compelling or memorable.

If there’s one stock character that I’m really sick of in video games, it’s the generic ally. This is a character who, early in the game, we are told has an existing relationship with the protagonist (lover / sibling / parent / child / lifelong friend / etc.) We spend the first chapter of the game following / escorting this person before they are kidnapped / killed / turned evil, and this serves as the main character’s motivation for the remainder of the game.

Let’s face it, this type of character is really just a half-assed attempt to toy with the player’s emotions. When this blatant ploy fails to generate a sympathetic response, the player is left with very little motivation to continue playing the game. It’s a crying shame too, because it takes an absolute minimum of subtlety to “fool” most players into caring for an NPC.

I can think of no better example of this type of subtlety than two of my favourite RPG NPCs: Ness’s parents from Earthbound.

Unlike other RPGs where the main character’s parents gab on and on about a family destiny or sacred honour, Ness’s parents are very minimalist NPCs. Indeed, they only have a few unskippable lines of dialogue in the opening scenes before you depart to save the world from Giygas. In any other RPG you’d have forgotten about them by the time you reached the second town. However, in Earthbound you stay in constant phone contact with mom & dad throughout the game. This isn’t accomplished by some disconnected conversation mechanism either, but rather by wrapping your interactions with them in gameplay mechanics.

Playing the game, you’ll definitely end up calling Ness’s father more than anyone else. He is given the utilitarian function of saving your game. He also deposits money in your ATM account for every monster you defeat, which is the only real source of income in the game (besides selling items.) It’s worth noting that Ness’s father never actually makes an appearance in person, likely a comment on the Japanese work ethic.

Ness’s mother has a much more interesting role in Earthbound. After a certain amount of time away from home, Ness can develop a status condition called “homesickness” that causes him to freeze up during fights. Attempting to cure this condition at a hospital results in the following reply:

What a sad look in your eyes… you, the boy in a red cap. You must be homesick. That’s nothing you need to be ashamed of. Anybody who is on a long trip will miss home. In this case, the best thing to do is to call home and hear your mom’s voice.

Indeed, the only way to cure this condition is to put in a call to Ness’s mom. With a few comforting words, Ness is back in fighting form. (If you’re reading this, call your mother right now! You know she’d love to hear about how you’re doing.)

Wrapping character interactions in game mechanics is an easy way to slowly develop organic relationships that don’t feel rushed or fake.

Games can also forge meaningful relationships between characters by making “empty vessels” that are ready to be filled by the player’s imagination and expectations. In the case of Earthbound, Ness’s parents are given minimal personality traits because the player is expected to internally substitute them with his or her own parents.

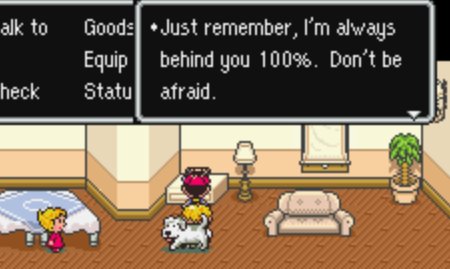

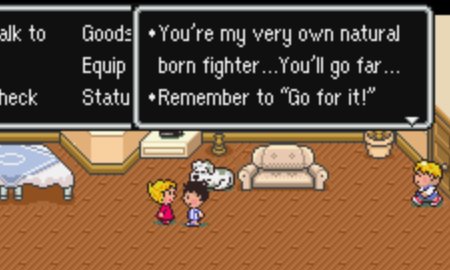

Ness’s parents play a very small role in Earthbound, but when they do become involved it is entirely to provide Ness with either material or emotional support, often from far away. His mother constantly reminds her son that she’s proud of him, and his father reminds him to “not work too hard” every time the game is saved. Furthermore, whenever Ness returns home his mother offers to make him his favourite dish. Except it’s not really his favourite dish, but rather yours, as defined by you at the very beginning of the game. The aim of this unconditional love and support is likely to remind the player of their own childhood experiences, or the experiences they wished they had.

Many have argued that Earthbound is either an allegory for growing up or a commentary on a child’s view of the adult world. If this is true, then causing the player to identify Ness’s parents as their own makes perfect sense. In general, creating characters that players can easily project characteristics onto is a simple way to make memorable NPCs.

In conclusion, while there’s really no exact science to creating unforgettable characters, I believe Earthbound is an excellent case study in storytelling minimalism. The fact that to this day a 16 bit SNES game that sold poorly in North America still has legions of dedicated fans is a testament to this greatness. The game is an experience like no other, and I hope this entry has given you a small glimpse as to why.

June 26th, 2008 at 5:55 am

Wow! Great write up, Mr G! I’m gonna have to get me some Earthbound action soon… I’ve barely heard anything about it, but every time someone mentions it, it keeps sounding better and better.

June 26th, 2008 at 9:33 am

@Ben: It’s definitely worth a shot, it’s the sort of timeless RPG that’ll still be a joy to play decades from now. The only turn-off might be that it’s a really old-school game, so the combat is actually rather difficult and your inventory has to be somewhat micromanaged. However, I’m sure an experienced gamer like you can handle it.