Back in 2020, I wrote about co-heading the accessibility effort on The Last of Us Part II and the incredible reaction to our expansive set of features. Later that year we were also honoured to receive the inaugural “Innovation in Accessibility” award at The Game Awards. In the years since, we’ve seen awareness and support grow for accessibility across the games industry, and many new games that have pushed the frontiers in novel and exciting ways.

More recently, I had the incredible opportunity to step into the role of game director on The Last of Us Part I remake for PS5. While our goal was to stay faithful to the original in terms of story and core mechanics, we had a chance to integrate a decade of technology and craft improvements to modernize the gameplay. This of course included accessibility.

In addition to porting over options from Part II, we developed a handful of new features for the remake. The most ambitious was providing descriptive audio for the cinematics. These were developed in partnership with Descriptive Video Works, who brought professional expertise from the world of film and television. We also developed a new DualSense controller feature that plays spoken dialogue as haptic vibrations, with the goal of conveying the cadence and emphasis of the actor’s performance without audio.

I was thrilled to be able to showcase the accessibility features in the game’s marketing. We released an accessibility feature highlight trailer, as well as Naughty Dog’s first audio-described story trailer. I also had the opportunity to discuss these features (and accessible design more generally) in interviews with Eurogamer, Fanbyte, and The Inverse. The Washington Post also featured a great story about players with disabilities who were excited to experience the original game without barriers that might have excluded them.

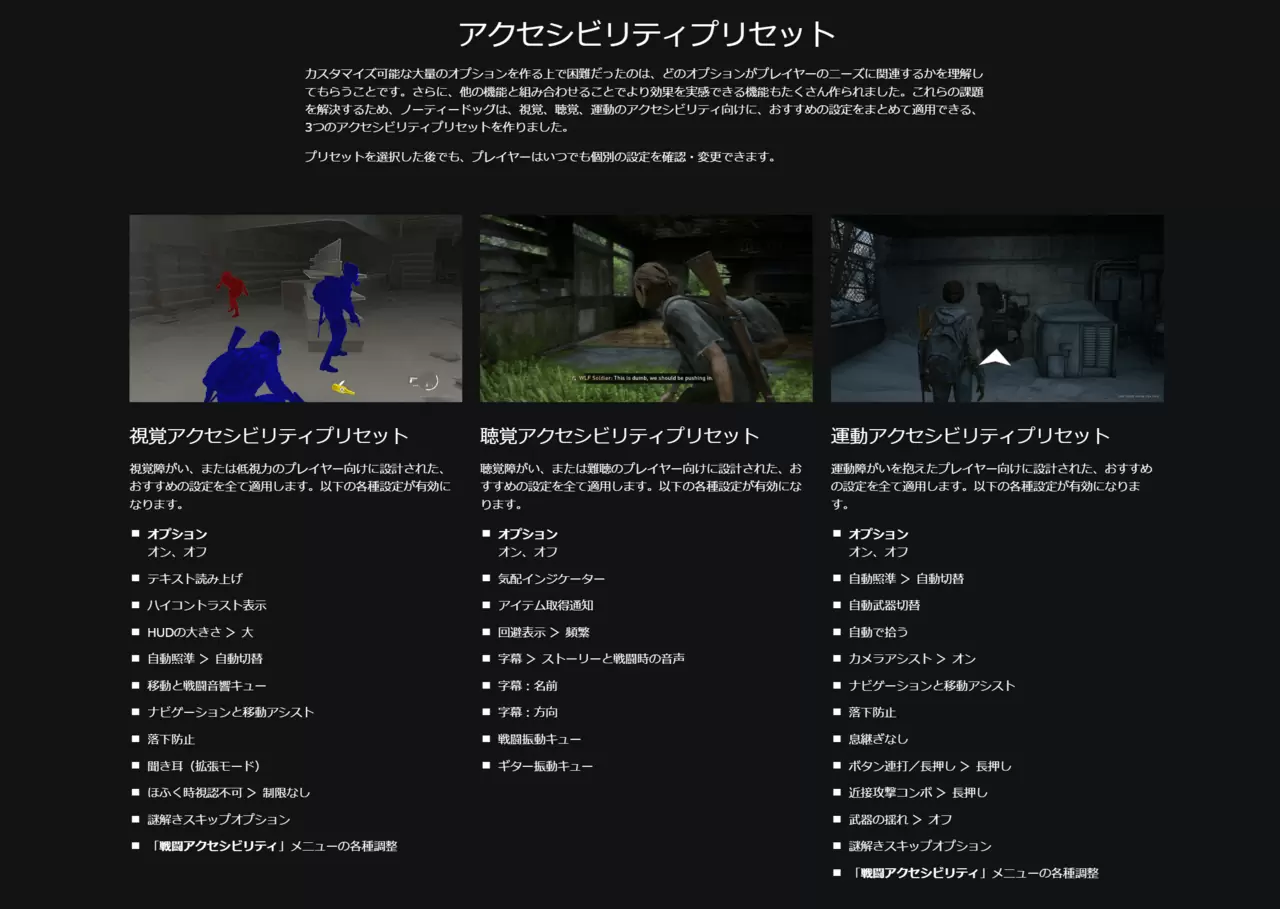

Finally, I had the unique opportunity to discuss accessibility with Den Fami Nico Gamer, one of the premier video game magazines in Japan. It was published alongside an interview with Hiromi Wakai about the accessibility features built into the PS5 OS.

Den Fami Nico Gamer – Will we be able to play games when we lose our eyesight or can’t move our hands?

For the benefit of non-Japanese speakers, I have provided my full original responses in English below, since automated web translation loses a lot of the details and jargon. (The translations of the questions were provided by Sony PR, and I have lightly edited them for clarity.)

Could you tell me reasons why you decided to support accessibility in your games? How do you decide which titles to support and which not to?

Accessibility welcomes players who wouldn’t otherwise get to play. While we specifically aim to support players with disabilities, the broader truth is that accessibility is good universal design for everyone. For example, subtitles are useful for deaf players, but I use subtitles if I’m playing games late at night while my daughter is sleeping. If I break my arm, I might temporarily need to use motor accessibility features while it’s in a cast.

Disability is extremely common (1 in 20 adults in Japan are considered to have some type of disability), and for all of us it is an inevitable part of our own mortality. Our vision, hearing, and motor coordination are all affected by aging. If the generation that grew up with video games wants to continue playing them into their old age, games will need to serve their changing needs.

We strive to support accessibility for all of our titles, and to continuously develop new technology that we can carry over to future games.

Before you start development, what did you start with and what did you research?

There are many excellent free resources that outline the most common issues and best practices for inclusive design. For example, the Access Design Patterns framework gives names to specific high-level design principles. “Second Channel” suggests that a visual cue in a game should be matched with an audio cue, and vice versa. “Clear Text” means providing options to improve legibility through colour, size, and contrast.

With these principles in mind, we begin designing and prototyping new features that we think would be useful. While most developers on the team are able-bodied, we can imagine playing the game without sound, without visuals, or only pressing one button at a time. However, we make sure to always invite players with disabilities to come playtest the game, provide feedback, and validate our feature ideas.

Development may cost higher and take more time to support accessibility. How did you persuade and secure the publisher with this in mind? Does the request come from the publisher side asking to support accessibility?

When we look at the big picture, the development cost of supporting these features is very small compared to the overall game production. The benefit is that it allows us to expand the audience for our games, bringing in new players who might have otherwise been excluded. Being able to modify settings to suit their needs allows all players to experience the gameplay more comfortably, without cumbersome barriers getting in the way.

In software and video games, features tend to be cheaper and easier to develop if you plan for them early in production. By being proactive about accessibility considerations, we ensure that they’re a natural and integrated part of the development plan, not something we’re having to scramble for at the end.

We are very thankful to have the full support of the studio leadership at Naughty Dog, and also from our publisher SIE. They recognize the importance of creating games that welcome players with many different needs and abilities.

I think it is very tough to decide how far to support [accessibility]. What did you do when you had to decide to limit some of the support? It would be great to ask about the thought process behind it.

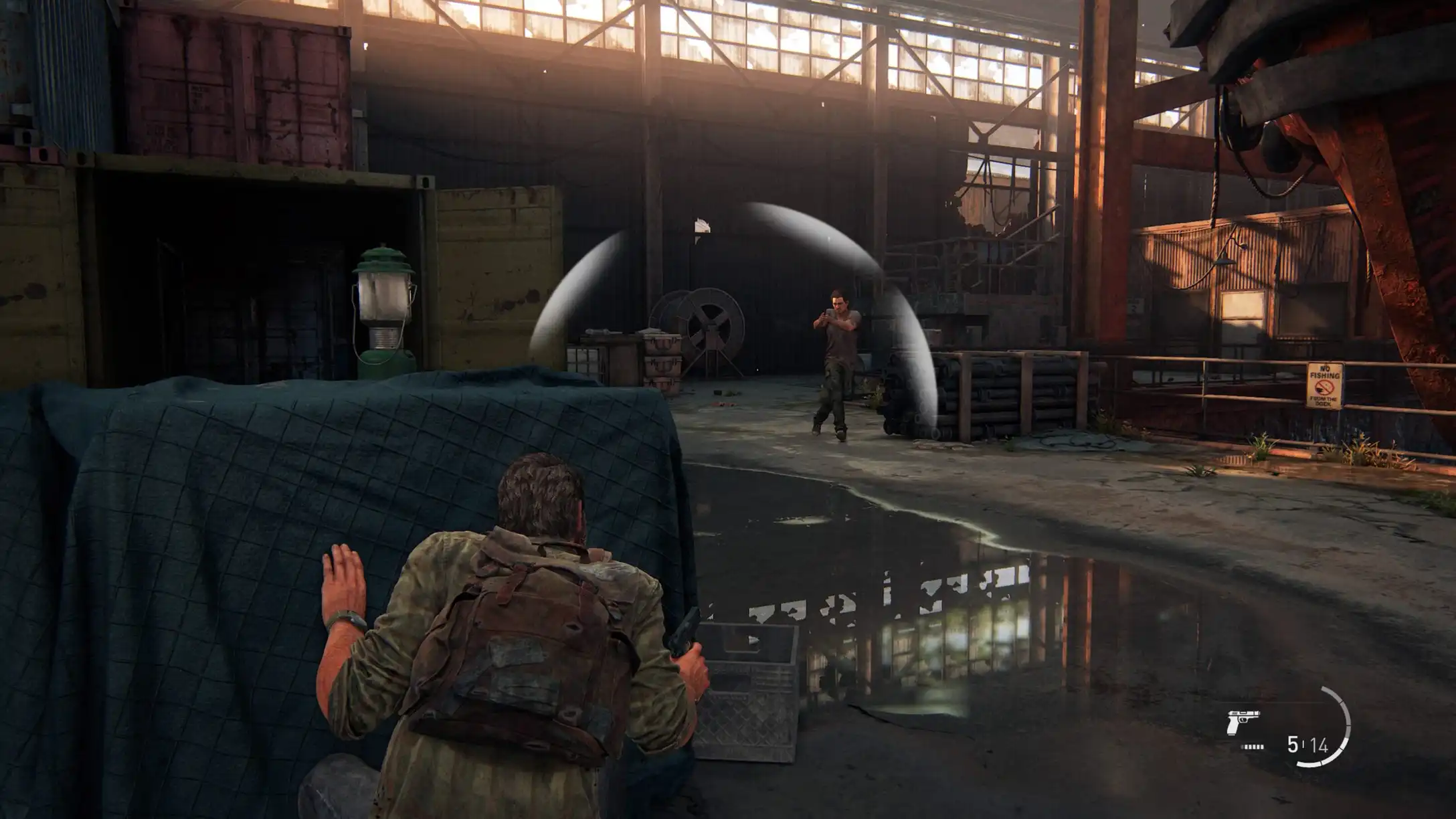

When we started development for The Last of Us Part II, the team decided to pursue four big accessibility goals based on technical feasibility and player feedback from previous games. The first was to offer fully customizable controls through button remappings. The second was to make our user interface (UI) and HUD elements dynamically scalable to larger sizes. The third was to provide a high contrast render mode that highlighted important visual elements for players with low vision.

Our last big goal was the most challenging and ambitious: we wanted players who are totally blind to be able to complete the game. We had recently heard a talk by accessibility consultant and blind gamer Brandon Cole, and he amazed us by showing how he was able to play games like Killer Instinct and Resident Evil 6 entirely through sound. We wanted players like him to be able to play our game too.

Because we aligned on these goals early on, it provided boundaries that safeguarded us from continuously adding new features. If we had a new exciting accessibility idea that didn’t match these goals, we could put it aside for consideration on a future game. We’ll keep striving to reach further with each game that we create.

Generally speaking, I think one of the selling points of PlayStation is the beauty of graphics. I think it is one of the most expensive parts of game development. Supporting [blind or low vision] users would mean to cut back on that strongest selling point, were there any dilemmas or struggles on those decisions? Were there any points of innovations or difficulties when trading off the graphical beauty for accessibility?

We take great pride in our visual art, so developing a new high contrast render mode that flattened and simplified all those finely-crafted details wasn’t something we took on lightly. The team made great efforts to ensure that the final result, while primarily functional, was still aesthetically pleasing and up to Naughty Dog’s artistic standards.

There are also many aspects of our games that can be appreciated without sight. We have a world-class sound team, and The Last of Us Part II won several awards for its audio design and music. Players also enjoy the combat challenge; blind gamers have beaten the game on the hardest difficulties. Of course, most players come to our games for the storytelling, which is still a powerful and moving experience with the voice acting alone.

When developing games, I think it’s important to have [people with several types of disabilities] to actually try out the accessibility features. Can you describe the framework you set up for the process?

There is a saying in the disability community: “nothing about us without us”. Throughout development, we periodically invite accessibility consultants to playtest the game. They provide critical feedback on our features and prototypes, letting us know what is working well and what needs further refinement. They also identify barriers we may have missed, and help us brainstorm new ideas to address them.

Were there any skills or requirements for the [accessibility consultants]? [Do they require] special school / vocational training school in order for them to supervise accessibility features in games?

Some accessibility consultants come from a background in user experience (UX) or human–computer interaction (HCI) design. They bring in knowledge of best practices from outside the games industry, such as subtitle guidelines from the BBC or the screen reader technology on the iPhone.

Consultants also bring in a wealth of communal knowledge from gamers with disabilities. If we’re discussing a particular feature, they can give us examples of good (and bad) implementations in other games, or share feedback they’ve heard within the community.

I hope to continue to see accessibility supported in games and hope to see more in the future. What were the positives / negatives that resulted from supporting accessibility?

We were incredibly excited by the positive reception from the breadth of accessibility features in The Last of Us Part II. We were surprised when the coverage even spread to major non-gaming publications, such as NPR and USA Today. We were also incredibly honoured to receive the inaugural award for “Innovation in Accessibility” at the Game Awards. We hope that this helps promote awareness across the games industry of the importance of accessibility.

More importantly, we received so many wonderful emails and letters from players. They said how excited they were to share the experience with loved ones. They recounted how they’d triumphed over boss battles without requiring able-bodied assistance. Nothing makes me prouder as a game developer than hearing these incredible stories.