The project that became Norwegian Wood began in late April of this year. With school winding down and the weather heating up, I felt the itch to tackle something new. By chance I had met a number of like-minded people over the winter; students with big ideas and aspirations of working in the game industry. Inspired by this collective potential, I decided to reach out to my local friends and colleagues about coming together to make a game over the summer.

The response was overwhelming; of the nine people I had e-mailed, seven of them were interested in participating. The project was suddenly much larger than I had anticipated, but I didn’t have the heart to turn anyone away. The eight of us (Kira Boom, Thomas Hibbert, Phil Jones, Renaud Bédard, Alex Charlton, William Mitchell, Kyle Sama and I1) formed the facetiously titled collective No Fun Games.

You might be surprised to learn that our original game idea had nothing to do with music, shoot ’em ups or The Beatles. While we explored a number of different game ideas, we settled on creating a murder mystery game set in an JRPG-style lumber town. We gave the development version the nickname Pulp2.

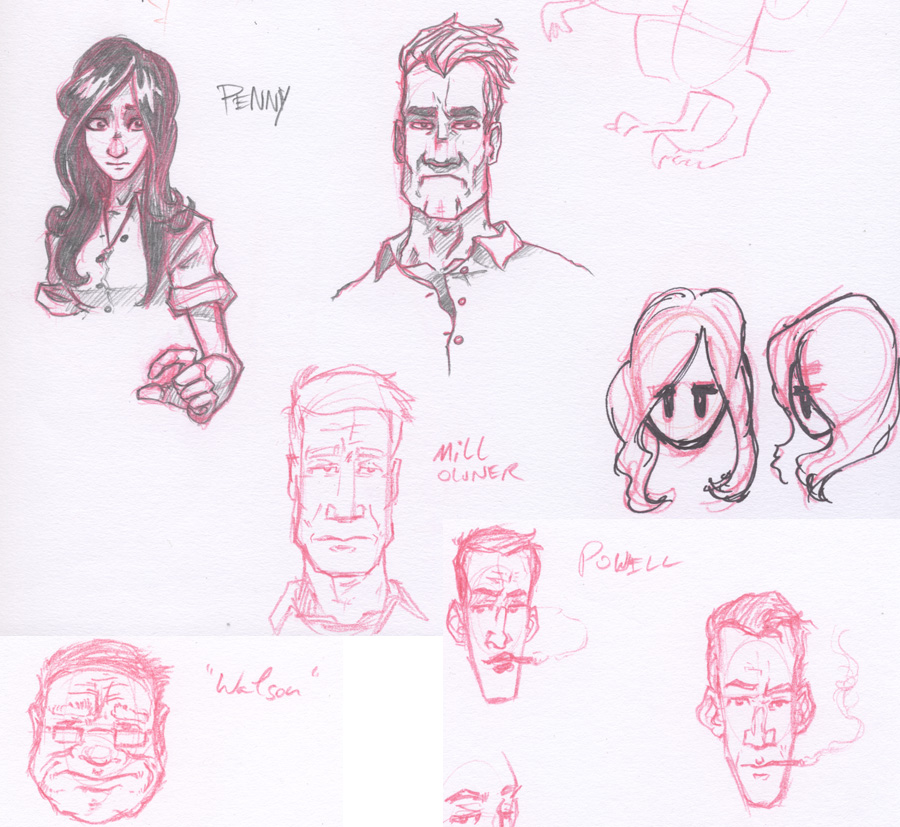

Pulp‘s main character was “Penny”, a local girl with a knack for mysteries. She teamed up with retired Sherlock Holmes analogue “Detective Powell” to solve the murder of his former partner “Dr. Watson” (we never really settled on official names). You can see Phil’s concept art for some of the characters above.

We developed an elaborate back story which outlined the motivation behind the murder and its connection to the protagonists. However, our ideas for the game’s actual plot and structure were little more than a skeleton. Truthfully, we possessed neither the inclination nor the talent to write good fiction and this was ultimately the game’s downfall.

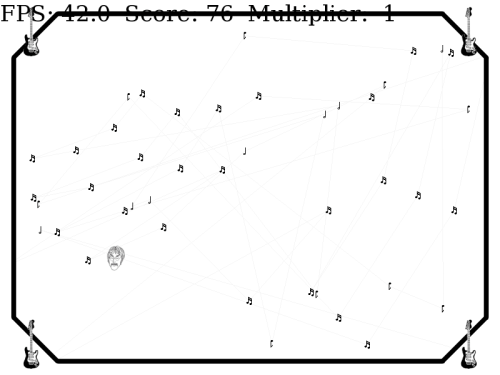

On the programming side, we put together a basic game engine in Python with the help of the Pygame and PyOpenGL libraries. It gave us the bare essentials, allowing us to add actors to the screen and assign them behaviours. As seen above, we created a simple world for Penny to run around and interact with (the Fez spritesheet was placeholder art lent to us by Renaud).

Sadly, this is as far as the Pulp project ever got. Despite our best intentions, we drifted apart over the summer. Everyone had personal commitments, internships, and travel plans. We simply didn’t have the time or motivation for leisure coding. By July, Pulp had reluctantly become vapourware. Fortunately, this wasn’t the end of No Fun Games.

By late August, things in my life were starting to slow down. I was back living in Montreal (after spending the summer at IBM in Ottawa), and had a couple of weeks off before the fall semester. Blessed with free time, I decided to reconnect with my teammates for a final sprint. Naturally, we wanted to release something after all our hard work.

Of course, not everyone had the luxury of time off. While we all wanted to participate, only Kira, Thomas and I had the hours to spare. Our artist Phil was also interested, but couldn’t commit to the heavy art demands of the murder mystery concept. With this in mind, we decided to drop that idea and reuse the engine we had created to pursue an entirely different genre.

The concept for Norwegian Wood came from our desire to explore the burgeoning intersection of music and gameplay. We wanted to create a game where listening and following the rhythm played a strong role in the player’s experience, but less directly than a game like Rock Band.

This idea manifested as a shoot ’em up game where the bullet patterns are timed to the individual instruments. The decision to use The Beatles’ music was somewhat incidental; I happened to be listening to Rubber Soul when the game concept occurred to me. However, the song has certain qualities that make it rather ideal. For instance, the notes are quite discrete, making it easy to divide the instruments and record timestamps. More importantly, using a calm lilting ballad with subtle dark undertones contrasted nicely with the upbeat synth-metal used in most shoot ’em up games.

Kira, Thomas and I got together at school to work on the game, working nearly full time for two weeks. We managed to create a playable prototype within a few days, then put the majority of our work into refining and iterating on the core gameplay. We also placed a strong emphasis on player feedback, bugging everyone around us to playtest it.

After chasing down the cross-platform bugs and ironing out the details of deployment, we finally released Norwegian Wood in late September. Thanks in large part to friends on Twitter spreading the word, we’ve had thousands of hits, hundreds of high scores and some very positive feedback. We’re thrilled that so many people have enjoyed our game, and promise to put all that excitement right back into making more of them.

To summarize in a brief postmortem, here are some lessons we learned during development:

What Went Right

1. Working Together Locally

While most of the work on Pulp had been completed remotely, it came at a cost to communication and motivation. For Norwegian Wood we decided that there is really no substitute for face-to-face time and met up in person every day. This was extremely effective, both for making consistent measurable progress and sharing a common creative vision.

2. Recording Global High Scores

The online high score table was a minor last-minute addition to the game. However, as Eric Swain pointed out in his insightful Indie Spotlight, it added a ton of value in terms of competition and replayability. “Even after all these years and innovations it is still a huge motivation to play. […] It isn’t all about competition, but the close knit community that get formed in that competition.”

3. Sidestepping Copyright

It took a lot of thinking to come up with a way to release a music game without infringing on The Beatles’ copyright3. Despite our doubts, having the user provide their own mp3 turned out to be a very successful strategy. Of course, it’s a shame that we picked the one band whose music can’t be downloaded legally. In the future, we’d very much like to reexplore this concept with Creative Commons licensed music.

What Went Wrong

1. Big Team Woes

Starting out with such a large development team on Pulp was a major challenge. Responsibility was spread too thin, and no one felt like they had creative control of the game on an individual level. In retrospect, I would recommend a team of no more than 4 for your first indie collaboration. Furthermore, it helps to have a fairly autocratic team leader.

2. Summertime Blues

I had assumed that summer would be the perfect time for students to pursue a side project. Working nine to five at an internship means having evenings off and lots of free time, right? Sadly, I was way off. The temperament of summer is lazy and leisurely; it’s hardly a season for picking up additional work. Furthermore, working full-time turns casual hacking into an unpleasant chore. Counter-intuitively, students would much rather attempt side projects while they’re juggling exams and assignments in the fall.

3. Storytelling Failure

We were incredibly naive about the process of writing a story for Pulp. We had the big picture ideas and the game mechanics, and just assumed that the moment-to-moment narrative experience would flow from that. We quickly discovered that writing a good story is an extremely demanding task, one we were ill-equipped to handle. Lesson learned: if you insist on having a narrative element to your game, make sure you have a dedicated writer (or semionaut) on the team.

Thanks again to everyone who was involved in Norwegian Wood, including those of you who playtested it and helped spread the word on release day. Making this game was a terrific experience, and it taught me a great deal about game design, programming and project management. I look forward to applying these lessons to my next game!

1 Ben Abraham was also briefly involved as music director, he wrote us a lovely dirge for Pulp.

2 Funny how Pulp turned into Norwegian Wood. The arboreal theme is coincidental.

3 Actually, Nick suggested this approach. Thanks Nick!

October 12th, 2009 at 8:26 pm

Wow, great to see how the mystery adventure turned into the amazing final product. The sitar is still my mortal enemy. =)

October 13th, 2009 at 8:19 am

Great writeup! I hadn’t noticed that the woody theme sticked by accident.

October 15th, 2009 at 6:17 pm

Wait a minute. Footnote 3…I came up with an idea?

October 17th, 2009 at 11:34 am

@Ben: It was quite the journey, we’ll definitely have to try collaborating again sometime.

@Renaud: Both names refer to dead trees too :O

@Nick: I was talking to you about this problem at the Polytron party, you suggested the drag-and-drop approach.

October 19th, 2009 at 2:03 pm

@Johnny: Good eye! That was also placeholder art ;)

October 19th, 2009 at 12:53 pm

The houses look an awful lot like the fortune teller huts from LoZ:ALTTP. I haven’t played it in ages though, so I could be wrong.

October 19th, 2009 at 2:40 pm

Also, where’s the RSS feed for this beast?

October 19th, 2009 at 2:45 pm

If you hit the RSS icon in your address bar, it should link you here.