Scott McCloud’s Understanding Comics continues to be a fascinating read. This is, in large part, because so much of his analysis of comics can be directly applied to video games, a new medium currently sorely lacking in critical vocabulary. McCloud has a knack for asking the right questions, and the further I read the faster the little wheels in my head begin to spin. The first chapter of the book asked the question “what is comics?”, which led me to question the definition of video games.

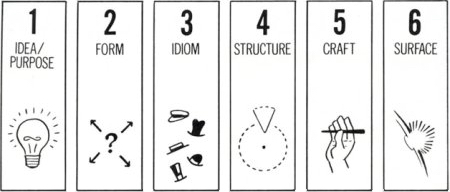

The second of McCloud’s concepts that I’d like to explore is his idea of the six elements of art (illustrated above). He believes that “any artist creating any work in any medium will always follow these six steps whether they realize it or not”, and that their order is innate. “All aspects of comics have the potential for self-expression” argues McCloud, “but the more a creator learns to command every aspect of their art and to understand their relationship to it” the more likely they are to focus on innermost aspects. Indeed, he makes the case that an artist’s skill is fundamentally related to the depth of their understanding in relation to these layers.

As they are innate to art itself, these six layers can also be applied to video games. I’d like to propose the following framework for how this might be done, using McCloud’s definitions as guidelines:

6. Surface: “Production values, finishing… the aspects most apparent on the first superficial exposure to the work”

In video games, this layer is best exemplified by cutting-edge graphics, sophisticated visual effects, high fidelity audio and overall technical polish (lack of bugs). These elements are very impressive, and can contribute greatly to the sense of immersion and suspension of disbelief. However, the surface is shallow and ultimately says little about the quality of the game.

5. Craft: “Constructing the work, applying skills, practical knowledge, invention and problem-solving”

The fifth layer (craft) is the realization of the concepts of the fourth layer (structure), and as such describes the concrete elements that make up a game. The aspects defined exclusively in this layer include:

- Level design

- Balance

- Difficulty

- Camera control

- Control layout

- Game feel

The key distinction in the fuzzy line between structure and craft is that the latter describes execution. For instance, I’m sure you’ve all played a game with a terrific concept that was ultimately made worse by sloppy controls, steep difficulty curves and poor level design. In other words, craft is to structure as engineering is to science.

4. Structure: “Putting it all together… what to include, what to leave out… how to arrange, how to compose the work”

The fourth layer describes the game in a conceptual manner, at the level of a detailed design document. It builds upon the skeleton defined by the first three layers, fleshing out abstract ideas into detailed systems.

What are the rules of this game? What is the role of the player, and how will they interact with the system? If there is a story, what is it about and how will it be told? Who are the characters? What will the art and music direction be? The structure of a game is defined by answering questions such as these.

3. Idiom: “The ‘school’ of art, the vocabulary of styles or gestures or subject matter, the genre that the work belongs to… maybe a genre of its own.”

While the value of legacy genre descriptors is highly questionable, in a general sense most games are deeply rooted in the paradigms established by their predecessors. For instance, modern first person shooters are the evolution of the vocabulary and perspective established by Wolfenstein 3D and Doom in the early 90’s. Mario Kart, Gran Turismo and Wipeout are very different games, but they share the common goals and language of the racing genre.

Of course, games should never be restricted by genre. Indeed, games that defy classification (Katamari Damacy and Indigo Prophecy are examples) deserve our attention, as establishing a new idiom is a feat of significant creative ability even if the game lacks craft or surface polish.

2. Form: “The form it will take… will it be a book? A chalk drawing? A chair? A song? A sculpture? A comic book?”

In a general sense, the form is the medium: video games. However, video games take many different forms: PC games, console games, handheld games, mobile games, etc. Each form has a unique identity, with idiosyncrasies, strengths and limitations, and usually addresses a particular audience.

1. Idea/Purpose: “The impulses, the ideas, the emotions, the philosophies, the purposes of the work… the work’s ‘content’.”

Put another way: what does this work mean? What is its thesis? What insights about life, the universe and everything does it communicate to the player?

Unfortunately, at this point in our medium’s history the answer is that most games mean very little. RPGs in particular classically have the veneer of “good vs. evil” or “value of friendship” morality lessons, but when the game mechanics revolve around combat and violence it’s clear that the commitment to these ideals is shallow. In reality, the thesis of Dragon Quest is closer to “fighting monster after monster until you’re strong enough to kill stronger monsters”. I love a good dungeon crawl, but consuming media with such shallow purpose is insubstantial and unfulfilling in the long run.

However, if we love video games, it’s because every once in a while a game crosses our path that speaks to us on a deeper level. A gem like Braid comes along and compels us, sending us in search of true meaning (fruitfully or otherwise). Games like System Shock, Planescape: Torment and Silent Hill 2 come along that give us meaningful experiences and reveal the exciting potential of this nascent medium.

In the future, I’d like to take the time to refine this framework and explore its implications for critique and design. For now though, I’d very much appreciate feedback and criticism both on my interpretation of McCloud’s six elements, as well as the basic premise that they represent.

January 20th, 2009 at 11:02 pm

I like this approach a lot: it’s a systematic way of exploring things that often defy empirical analysis. I haven’t read McCloud’s book, and your site is my only experience with his six elements, so please forgive any misinterpretations in my suggestions.

I am a bit hesitant to lump “lack of bugs” in with the sixth layer. Full disclosure: bugs in games are a pet peeve, but I still think their existence speaks to more than a surface level flaw. The worst bugs undermine the structure of the game, making it frustrating or even unplayable. Perhaps they should go in layer 4 or 5?

I think an argument could be made that a game’s idiom (as defined by the six elements) is often its structure. [Wolfenstein and Doom], [Mario Kart and Gran Turismo], and [Super Mario Bros. and LittleBigPlanet] differ greatly, but their idioms are similar largely because their structures are similar. The “paradigms” they share are rooted in their most basic rules. As you can tell, Jorge and I have been grappling with whether we can decouple genre and gameplay, and it has proven to be a tricky feat.

Perhaps idiom is an important layer because it prevents structure from becoming too rigid, but I feel like as they stand now, the two layers could be combined.

Anyway, those are my initial reactions, and I’m interested to see what kind of discussion this starts. I’ll definitely be referencing this framework as I play games.

January 21st, 2009 at 12:38 am

You’ve read the MDA paper, yeah? If not, give it a read (http://www.cs.northwestern.edu/~hunicke/MDA.pdf). It’s quite similar and if six layers above were to be slightly combined or tweaked, it would look the same.

I think these are great models, as it can help focus efforts in the appropriate areas to achieve desired results. Maybe I’ll have to give McCloud’s book a read.

January 20th, 2009 at 11:43 pm

I like this very much.

One part especially resonated with me: “[…] establishing a new idiom is a feat of significant creative ability even if the game lacks craft or surface polish.”

I think this applies to all of the layers here. I would propose two things: first, as you move down this list, it becomes more difficult to innovate; second, given sufficient creativity, all layers above the one you innovate on are granted leniency if they’re subpar.

For example, Grim Fandango had fantastic characters, story, art and music (layer 4), so I was willing to forgive the occasionally ridiculous puzzles (layer 5) and the buggy controls (layer 6).

January 21st, 2009 at 1:51 pm

@Scott: I think it depends on the severity of the bug. If it’s a minor graphical or stability related bug, then it’s a surface issue. If the bug causes the AI to break or messes up the difficulty curve, then it’s a craft issue. I can’t imagine how a bug could be traced back to the conceptual ideas of the structure, unless it’s a fundamental logic flaw in how the game works.

While I see your point about idiom and structure being strongly linked, I think coupling them in any way would be a disservice to the innovative games that establish genres. As Dan said in his comment, “as you move down this list, it becomes more difficult to innovate.” While a game’s basic rules are part of its structure, it’s important to recognize when they are derived from and built upon the work of others.

@Dan: I completely agree, and I think this is the reason why experience gamers often value novelty over quality. They recognize the importance of new ideas and idioms.

@Nels: I was not aware of the MDA paper. I’ve bookmarked it for future reading, thanks :) Understanding Comics comes highly recommended, I hope you enjoy it.

January 22nd, 2009 at 7:03 am

Since I read this yesterday, something’s been eating at me about it, and I’m having trouble figuring out what it is, but I think this is it:

“In reality, the thesis of Dragon Quest is closer to ‘fighting monster after monster until you’re strong enough to kill stronger monsters’. I love a good dungeon crawl, but consuming media with such shallow purpose is insubstantial and unfulfilling in the long run.”

You go on to mention Braid, Planescape: Torment, Silent Hill 2, and System Shock as the types of things that would be examples of, I suppose, “fulfilling” games. These are all games with deep, meaningful narratives, the kinds of stories that truly touch players, and I certainly can’t argue against them. My question is: what is the place of something like Guitar Hero? I’d say that Guitar Hero “give[s] us meaningful experiences and reveal[s] the exciting potential of this nascent medium,” but it does so without a narrative, without real potential for emotional investment other than that which we choose to put into it for the sake of challenging ourselves.

Similarly, I’d go so far as to call Dragon Quest a great work of art, despite its lack of meaningful narrative; its “feel”, its appearance, and the way it guides/limits the player’s exploration were ground-breaking for their time, and the experience of playing it is etched much more distinctly in my mind than my time playing System Shock, despite my utter love and devotion for the latter.

If the ideals you lay out hold, can you still have great art with a hollow apple?

January 28th, 2009 at 4:41 pm

@Mike: Sorry for taking ages to reply to your comment, I was at CUSEC last week and I’ve been playing catch up ever since.

In Understanding Comics, McCloud considers layers 1 and 2 to be equally important starting points for artistic expression. Beginning with an idea asks “what does this work say about life through art?”, while starting with form asks “what does it say about art itself?”

While it might be a bit of a stretch, it could be argued that perhaps rhythm games such as Guitar Hero and Rock Band would fall under the latter category. By expressing the art of another medium (music) through video games, we’re shown an entirely different side of these works. The fact that these games require unique custom peripherals to play certainly supports this idea.

As for Dragon Quest, I believe that it was historically important and ground-breaking in defining the idiom of RPGs, but I would not classify it as a great work of art. This statement deserves hundreds of words to support it, but I would suggest the following framework for arguing it:

DQ was extremely innovative in the 80’s, but today these innovations have been absorbed into the collective unconscious of gaming. Beyond historical appreciation, there is little reason for a gamer to revisit Dragon Quest. It offers no insights on life or art, and is mired in the conventions and mistakes of the era. Simply put, the game itself lacks a timeless quality that I believe is a property of great works of art. The gameplay innovations that it offered, however, will live on in its imitators for decades to come.